Tulun himself was a Turkish slave from Bokhara who was given to Caliph Mamun in 815 AD as a present. Afterwards, he became a powerful and influential person in the court of Mamun, allowing his son Ahmad Ibn Tulun (ibn means son of) to be well educated in the best traditions of Islamic law and government. As a young man, Ahmad was a loyal servant to his caliph in Samarra (north of modern Baghdad), Mesopotamia and when his father died and his stepfather was given Egypt as a sort of private estate by the caliph, Ahmad Ibn Tulun was sent to administer the country.

Ibn Tulun's appointment as prefect of Egypt came in 868 and at the end of a long period of political strife. The Bashmurite rebellion of 832 in the Nile River delta between the river's Rosetta and Damietta branches was the last and most violent of the Christian uprisings in Egypt. Caliph Mamun himself has spend forty-nine days in Egypt taking part in its suppression. Maqrizi, a well known historian of that period, says that, "From then on, the Copts were obedient and their power was destroyed once and for all; none were able to rebel or even oppose the government, and the Muslims gained a majority in the villages". In 853 the Byzantines successfully attacked Damietta, and then from 866 to 868 AD and Arab-led revolt smoldered in a vast region of the delta and Fayoum.

When he arrived in Askar-Fustat (which would one day spawn Cairo), at about the age of thirty-three, it is said that he was unable to even pay his way from Baghdad to Egypt. He had to borrow ten thousand dinars to set himself up in his new position. That soon changed, however, for by 870 he was well enough off to build his own capital, because old el Askar was too small for his entourage of soldiers, ministers, wives and slaves.

When he arrived in Askar-Fustat (which would one day spawn Cairo), at about the age of thirty-three, it is said that he was unable to even pay his way from Baghdad to Egypt. He had to borrow ten thousand dinars to set himself up in his new position. That soon changed, however, for by 870 he was well enough off to build his own capital, because old el Askar was too small for his entourage of soldiers, ministers, wives and slaves.He built this city on a little knoll of high ground between Fustat and the Mukattam Hills, called Yeshkur. The political power of the Tulunids, the flowering of their art and the pomp of their court life were expressed in this new capital. Today, this area of the city is not difficult to find, for atop the little hill Ibn Tulun built his famous mosque which has survived the devastations of time. The new city was built just northeast of el Askar and its boundaries were the Mosque of Ibn Tulun on the east, Birkat al-Fil (Pond of the Elephant) to the north and the sanctuary of Zayn el Abidin to the south. It has been estimated that the new city took up some 270 hectares of land.

It is said that this was a Christian cemetery where Moses was supposed to have had a conversation with God, and where Abraham slew his sacrifice. Muslims considered it a holy place, since Christians and Jews were both respected by Islam as "people of the Book". However, Ibn Tulun cleared the Christian graves from the area and built his royal capital around the hill. This new town was divided into special katais (districts) for each segment of the population who came there to live. Each of these districts was then named according to the kind of population, consisting of servants, soldiers, guards, Romans (actually Greeks) or Nubians. Hence, the city was called Katai (al-Qatai, the districts, the wards or the plots). This by the way was a tradition from Samarra, which was likewise divided into districts. There, Ibn Tulun built a palace (qasr) at the foot of the Mukattam Hills, a garden, a racecourse and polo grounds, a zoo, a palace for his wives, baths, a hospital and rich houses for his staff. A road led from the palace and the square to the mosque and the "Main Avenue (Shari el Azam), which possibly coincides with that would become Saliba Street. Now the city that would become Cairo consisted of three capitals built by three rulers, consisting of Askar, Fustat and Katai, and with Ibn Tulun, it began to take on the decorative style that made it a genuinely fabulous place.

It is said that this was a Christian cemetery where Moses was supposed to have had a conversation with God, and where Abraham slew his sacrifice. Muslims considered it a holy place, since Christians and Jews were both respected by Islam as "people of the Book". However, Ibn Tulun cleared the Christian graves from the area and built his royal capital around the hill. This new town was divided into special katais (districts) for each segment of the population who came there to live. Each of these districts was then named according to the kind of population, consisting of servants, soldiers, guards, Romans (actually Greeks) or Nubians. Hence, the city was called Katai (al-Qatai, the districts, the wards or the plots). This by the way was a tradition from Samarra, which was likewise divided into districts. There, Ibn Tulun built a palace (qasr) at the foot of the Mukattam Hills, a garden, a racecourse and polo grounds, a zoo, a palace for his wives, baths, a hospital and rich houses for his staff. A road led from the palace and the square to the mosque and the "Main Avenue (Shari el Azam), which possibly coincides with that would become Saliba Street. Now the city that would become Cairo consisted of three capitals built by three rulers, consisting of Askar, Fustat and Katai, and with Ibn Tulun, it began to take on the decorative style that made it a genuinely fabulous place. El Katai was surrounded by a network of narrow streets and it is said that there were eventually a hundred thousand houses in this city. It had lush gardens and zoos, along with many gates (said to be nine) into the square. Each of the gates had a special meaning and each a special name. One could only enter by the gate of ones class or profession, though who classified this large population we really don't know. There was a Gate of Nobles and a Gate of Lions, surmounted by two carved lions, and a gate called el Darmun because that was the name of the captain of the guards. Ibn Tulun himself entered through a special tri-arched gate of his own known as the Hippodrome, and when he reviewed his troops he would lead them through the center of it while up to thirty thousand men would pass through the side arches.

Of the palace that Ibn Tulun built nine years earlier than his mosque, nothing now remains, for his later rivals razed it to the ground. Surviving sources indicate that it was built to challenge the splendors of Samarra, and like the palaces of the city, it to was immense in size and boasted gardens. The palace was located next to the Hippodrome and was known as the 'Palace of the Hippodrome'.

Of the palace that Ibn Tulun built nine years earlier than his mosque, nothing now remains, for his later rivals razed it to the ground. Surviving sources indicate that it was built to challenge the splendors of Samarra, and like the palaces of the city, it to was immense in size and boasted gardens. The palace was located next to the Hippodrome and was known as the 'Palace of the Hippodrome'.The hospital that Ibn Tulun built between 872 and 874 AD, known as a muristan, could be counted as modern even now. One would leave their own clothes when entering it and put on hospital garments. All food and medicines were free, and Ibn Tulun inspected the hospital every Friday. This hospital was built specifically for the general population, and in fact his soldiers and guards were forbidden from its grounds. Tradition holds that the hospital was built with money (60,000 dinars) from a treasure trove found by one of Ibn Tulun's servants in Upper Egypt. The servant was riding in the country one day when his horse fell into a hole, and in the hole they found treasure worth a million dinars. This is not an uncommon story in Egypt, for more than one treasure has been discovered in this manner. The hospital was further endowed with the inalienable right to the profit from the slave market and other large and prosperous markets.

To supply this new city with water, Ibn Tulun built an aqueduct, at a cost of 40,000 dinars, of which several arches are still extant between Birkat el Habash and the palace.

The mosque that Ibn Tulun built and which survives in Cairo must be one of the most beautiful and stimulating monuments any historical figure has ever managed to leave behind him. Its intrigue is only matched by a story about its founding. It is said that Ibn Tulun did not want to rob any more Christian churches of their columns because he thought it sacrilegious. However, he required a mosque of considerable size. Hearing of Ibn Tulun's problem, a Christian who was in jail for some minor offense offered to build a very large mosque with no columns, and he sent Ibn Tulun an outline showing a vast enclosed courtyard with the mosque itself held up not by marble columns but by squat brick piers supporting pointed arches. Ibn Tulun immediately grasped the inventiveness of the idea and freed the Christian, paying him 110,000 dinars for his work, which was not bad considering the mosque itself cost only 120,000 dinars.

This is a good story but scholars doubt its validity, believing rather that it was told to explain the use of brick piers, which had never before been seen in Egypt. However, fire was probably a concern, and marble disintegrates under flame, while brick does not. Another factor is that at Samarra, in the Tigris River basin, buildings were made from clay, so this would also explain the use of brick. Brick must be very cleverly used to be both imposing and beautiful, and there is something so powerful and individual in those brick piers, even now, with the famous pointed arches rising over them like a ballerina's swanlike arms, that even a layman can see the originality of this unusual design. This mosque was the first to use the pointed arch in a vast architectural complex, and it would be another two hundred years before Christians would borrow it for their own Gothic arch. The cloisters were also born in this kind of four-walled, colonnaded mosque. The whole concept of this complex, brilliant it would seem in almost every brick, probably owned its design not to a jailed Copt, but to mosques already standing in Samarra, but in style at least it is wholly Egyptian.

Ibn Tulun was not yet fifty when he got dysentery from drinking too much milk. He was in Anticon on a military expedition at the time, and was carried home to Fustat on a camel litter. His doctors put him on a diet, but he became violent and refused to obey them. In fact, when he was dying he had his doctors flogged to death for their failure, and by 884, he was gone.

Regrettably, Katai was a dynastic city that did not long survive the Tulunids who built and inhabited the city. The traveler Ibn Hawqal, who describes Fustat around 969, mentions its disappearance when he writes, "Outside Fustat, there used to be constructions built by Ahmad Ibn Tulun over an area of a square mile where his troops were quartered, and it was called Qata'i. It was comparable to Raqqada, which the Aghlabids founded outside Qayrawan. Both of these sites have today fallen into ruin. Of the two, Raqqada was stronger and better appointed". Simply put, Katari was too distant from the Nile, and could not develop as an autonomous economic center.

What to See

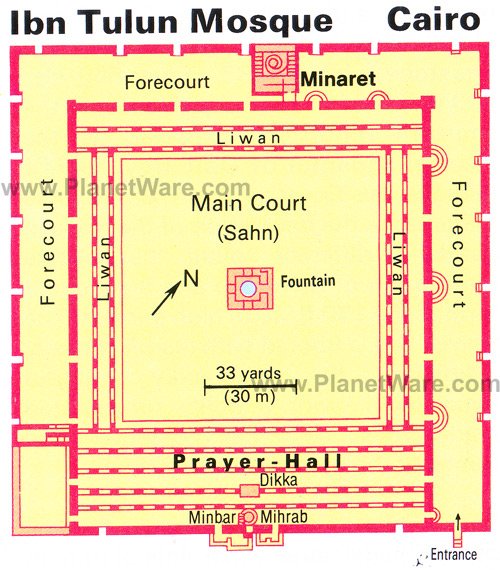

The entire complex of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun is surrounded by a wall and covers more than 6 acres. With an area of 26,318 sq m, the mosque itself is the third largest in the world.

The arches of the courtyard galleries are decorated with beautifully carved stucco, the first time this medium was used in Cairo.

The minaret, the only one of its kind in Egypt, is modeled after the minarets of Samarra, with a spiral staircase around the outside. Andalusian influence can also be seen in the horseshoe arches of the minaret windows and elsewhere - this was brought to Egypt by Muslim refugees who were driven out of Spain by the Reconquista .

The mosque has been restored several times. The first known restoration was in 1177 under orders of the Fatimid wazir Badr al-Jamālī, who left a second inscription slab on the mosque, which is noted for containing the Shī'ī version of the shahada, adding the phrase "And Ali is the wali of God" after acknowledging the oneness of God and the prophethood of Muhammad. Sultan Lajīn's restoration of 1296 added several improvements. The mosque was most recently restored by the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities in 2004.

During the medieval period, several houses were built up against the outside walls of the mosque. Most were demolished in 1928 by the Committee for the Conservation of Arab Monuments, however, two of the oldest and best-preserved homes were left intact. The "house of the Cretan woman" (Beit al-Kritliyya) and the Beit Amna bint Salim, were originally two separate structures, but a bridge at the third floor level was added at some point, combining them into a single structure. The house, accessible through the outer walls of the mosque, is open to the public as the Gayer-Anderson Museum, named after the British general R.G. 'John' Gayer-Anderson, who lived there until 1942.